Necessity to legacy

Published 11:10 am Thursday, February 4, 2016

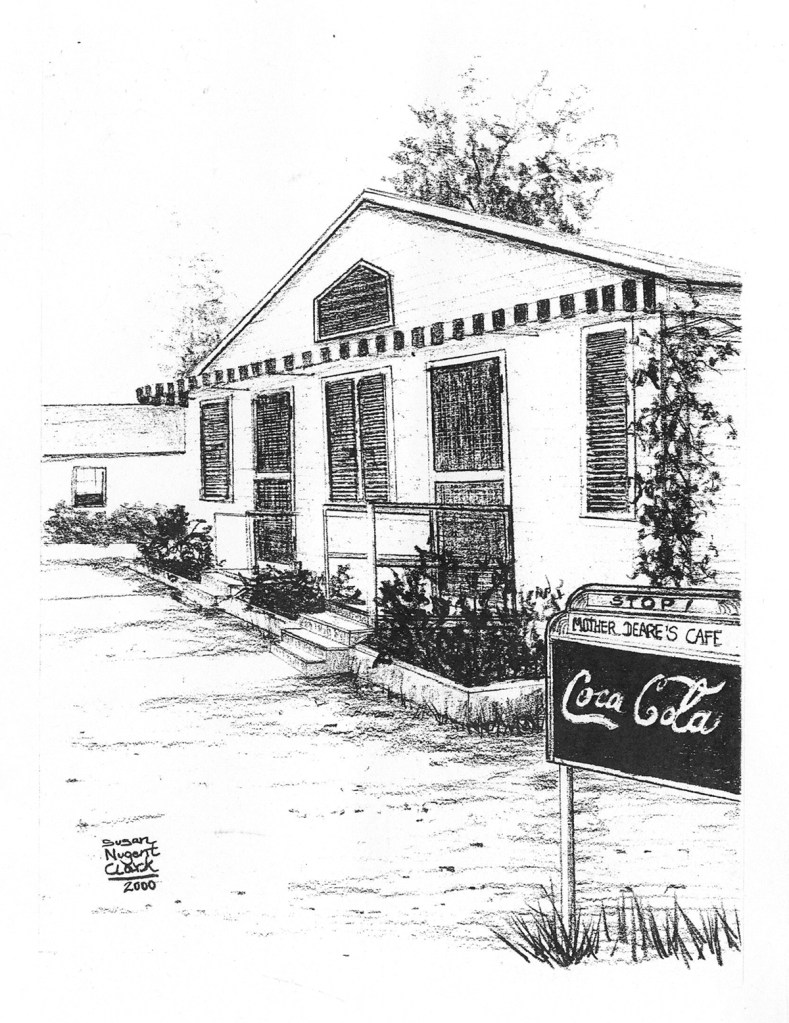

- Mother Deare, the nickname for owner Ola Katherine Kelly Deare, was a popular restaurant for many of the sugar cane workers staying at her next door boarding house as well as others passing through New Iberia, local residents and business workers near the Jane Street eatery. This drawing is by her great-granddaughter, Susan Nugent Clark.

Family cooking follows the generations

It’s not unusual for a restaurant to become famous for a particular food item, but in its heyday, Mother Deare’s was not only known for its biscuits, the endearing name also was home to many workers in the sugar cane mills. Her ancestors still carry on an appreciation for the delicacies once served to patrons during hard times.

“Mother Deare, during the grinding season, always ran a boarding house for the people that worked in the sugar mills,” said Ruth Nugent Boudreaux, 88, Mother Deare’s granddaughter. “In those days the men would come in from far away. My mother cooked for them, too, at Albania and Orange Grove Plantations. Mother Deare was a wonderful cook.”

Ola Katherine Kelly Deare had a house full of children. Boudreaux’s mother, Essie Florence Deare Nugent, was one of Mother Deare’s daughters. In the summers as a child, Boudreaux remembers going to Albania and Charenton, a summer place for the well to do.

Mother Deare would cook in the restaurant and Boudreaux’s mother would go and help. She said it was great for the kids. Those were the early years before Mother Deare’s opened.

“I started working in Mother Deare’s when I was 12 years old,” Boudreaux said.

It was still around when Susan Nugent Clark, great-granddaughter of Ola Deare, was a child. Raised in New Iberia, her father was Ruth’s brother Eddie. She said they would “play” at working in the restaurant before customers came in.

On the same property as the restaurant was the family home and a boarding house. The tenants would eat their meals at Mother Deare’s. Three buildings, two businesses, around where National was on Jane Street, Clark said, she was a woman before her time, a real entrepreneur. The big tree is about the only thing that’s left, she said.

Doing What Came Naturally

The actual beginning of the restaurant is not known exactly, but the descendants believe it started during the late 1920s or early 30s. Deare was an in-charge woman. When she shouted orders, Boudreaux said, “you better do it.” At the heart of her business were her biscuits.

“When they said Mother Deare, they said biscuits. I can still see Mother Deare at the table in the kitchen with a big aluminum pan,” Boudreaux said. “She’d pour 10 pounds of flour in. Never a spoon, she’d measure with her hand. So much salt, baking powder, shortening, all measured by hand. She would mix it up to the consistency she wanted, roll it out, really big, and flap it over onto itself. Then she’d cut the biscuits out and bake them.”

“She was like a mother to the men who came and stayed at the boarding house and ate at the restaurant,” said Julaine Schexnayder, another granddaughter of Mother Deare. “Men could walk from the train station to her boarding house, have a place to stay, eat and call on their customers in the area.”

Mother Deare also had a tonic she’d prepare for the oil men who would come into the restaurant with a hangover after a big night. She’d fix them tomato juice, hot sauce and something else Boudreaux couldn’t detect. She would shove the drink into their hands and say, “Take it,” Boudreaux said.

Boudreaux said Mother Deare made the best cream pies and pecan pies. The family and employees were not allowed to eat unless something was left over. Boudreaux remembers waitressing with her Aunt Pearl. Not long before the shift ended, Pearl told her to meet in the bathroom after the shift. She had stashed away pecan pie for the two to enjoy.

“For my birthday, Daddy (Earl Deare) would ask what kind of pie I wanted because Mother Deare was going to make me one,” Schexnayder said. “And she did.”

The Transition

After Mother Deare died, two of her children, Boudreaux’s mother and Clark’s grandmother, attended to business for a short period. Neither had the passion or calling to be a restaurant owner but some of the recipes live on.

“I looked and I looked for my recipes, but I had already given them to Susan,” Boudreaux laughed.

During the second World War, Boudreaux began to make cakes and cookies for friends and family to send to their children overseas. She would take orders, bake and pack to mail as a service for the family members.

She also catered coffee parties, beginning at $10 for the first event, Boudreaux said. After marriage and a lifetime of working in banking, she started baking pies as a sideline after retirement.

“When I started doing the pies, my husband had just died which was 12 years ago,” Boudreaux said. “Sometimes I’d have as many as 18 pies on the table. I’d charged a little of nothing to start. I made lemon, coconut and chocolate cream pies charging $5 a pie.”

Boudreaux would get orders by word of mouth popularity, but said it got to be too much so she had to stop. That was not long after one man ordered 15 pies he was giving to his customers.

The Next Generation

The art of cooking can be passed down from generation to generation. Appreciation of cooking and family history is just as important. Clark captured a moment in time with her own creativity as an artist in a sketch which is one of the few pictures remaining of Mother Deare’s.

Clark’s oldest son, Chris Warner, is another type of artist. He is a writer. One of his first books is a collection of Traditions of the college Southeastern Conference called “A Tailgater’s Guide to SEC Football.” In it he devoted a chapter to his younger brother who is a chef.

In “The ‘Art’ of Tailgating,” Chef Jeff Warner’s collection of recipes are dedicated to various SEC teams and their tailgating fans. His Louisiana offering is featured in today’s recipes.

Jeff Warner attended culinary school in Baton Rouge, worked three years as a chef on a paddelboat going up and down the Mississippi, was an executive chef for a catering company in Manhattan and other locations before landing the key position at The Bluffs in St. Francisville.

Although he is not directly carrying on Mother Deare’s tradition, her culinary talents have found a new home.

No one in the family has been able to find a recipe for Mother Deare’s biscuits, but the memory of eating the fresh confection along with fried chicken and fresh vegetables, may be familiar to some who remember the Jane Street landmark.

Schexnayder has a picture of Mother Deare at the old washpan she used for making biscuits. It was there she had a stroke and soon after died in 1958.

Today’s recipes are in her honor and all who were touched by the neighborhood eatery known as Mother Deare’s.