60 years of sugar cane work — and still devoted

Published 7:00 am Sunday, September 22, 2019

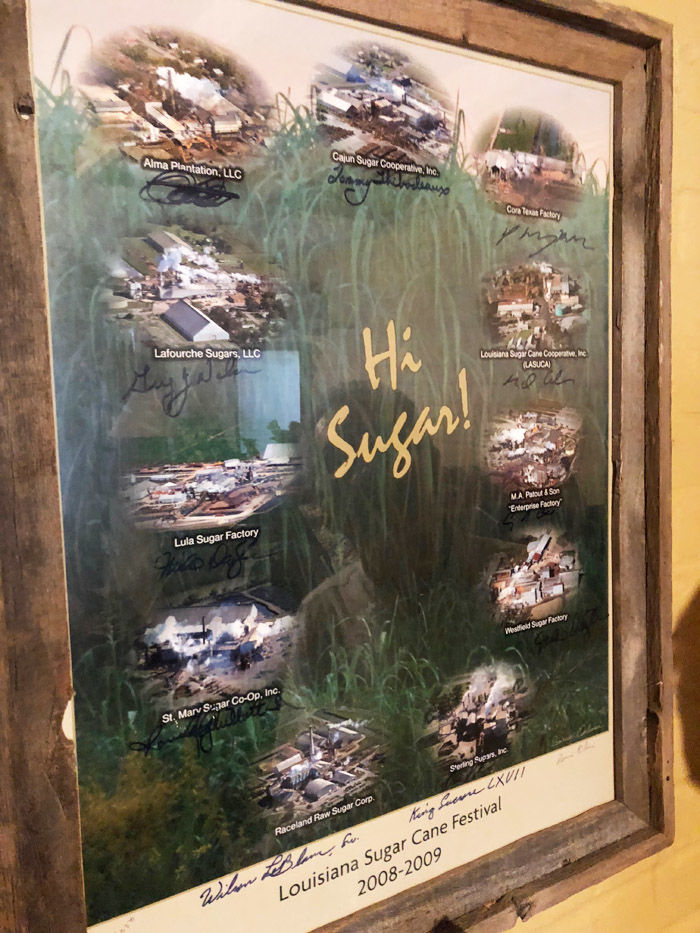

- Among Wilson LeBlanc's memoriablia is a signed poster from the 2008-2009 Louisiana Sugar Cane Festival when he reigned as King Sucrose LXVII. His reflection shadows the artwork of the poster.

Longevity and promotion for a job well done are not the norm they once were in business environments, particularly manufacturing. The first 50 years with M.A. Patout & Sons Inc. sugar cane mill brought a celebration that might have encouraged Wilson LeBlanc Sr. to take it easy. But for the man who has now spent 60 years in the mills, fields and industry surrounding the Teche Area and around the world, sugar truly is in his blood. Finally officially retired as of this summer, doesn’t mean staying idle at home. Still consulting, last week LeBlanc spent at least a portion of every day at one mill or another. The Louisiana Sugar Cane Festival, starting this week in New Iberia, will always have his participation as a former King Sucrose LXVII, the 67th in 2008.

Humble Beginnings

Trending

After the original mill caught fire and burned down from an electrical storm in March 1959, a young LeBlanc waited for hours for an employment interview that resulted in a job sweeping the shop floor. Ralph Olivier in the machine shop discovered he the young man could use a lathe, se moved him up to shaper work making keys on the mill floor. For $1 per hour, straight time, the first paycheck copy at the start of his many scrapbooks records his efforts — after taxes $26.32. Check No. 84 was signed by the man who would eventually become his work-related traveling companion for global consulting, William Patout Sr. Within two years LeBlanc moved up to mechanic and within four years was head machinist, taking care of pumps and turbines.

“They wanted to make something and didn’t have a guy. I said I can make it,” LeBlanc said. “I made it in just a few minutes. They said, how did you do this, but it was nothing to make that part. I’d gone to school to learn. Before you know it, I graduated up and they put me on the machines as a machinist. That’s where school pays off. From then on I studied from there to be a better machinist. The management saw it, gave me books and I studied during the noon hour, others were sleeping or taking a nap and I was at different machines. It didn’t take me long to move up.”

In 1963 LeBlanc married and was drafted into the U.S. Army, but his value was instrumental to the sugar mill and his supervisor, George Smith, got a deferment for grinding season. Then he went into the National Guard with a six month active duty assignment. When he returned, the job was waiting for him with a 35-cent per hour raise thanks to David Bailie who recognized his worth.

Demand Moves Mills

Working in the mills as a mechanic, moving up as people retired, learning by necessity and even planned extended educational opportunities were always at the discretion of his upline bosses and mill owner. Technology was changing in the mid-1960s and so was his life. LeBlanc took one day off in 1966 when his first child was born but was chastised by a new chief engineer who was vary unhappy that LeBlanc missed work.

More energy power was needed as the mill and equipment demands grew. By 1972, LeBlanc was the number two man in the factory, the assistant chief engineer. By this time he was studying mechanical drafting at night and designed a new style cane table and a special machine which he drew and built. Around the same time, Billy Patout, son of the company owner, returned from Haiti to train under the general manager slated for retirement.

Trending

“They had spent a lot of money to get to the 5,000 tons of cane capacity and didn’t make it,” LeBlanc said. “I remember the management asking me, ‘What would it take, how much money to get to that level?’ I said, I think you have a pretty good factory, but you gotta fix it right. You don’t have to spend any more money, we just did it right. We winded up grinding way over 5,000 per day.”

Travel to other mills around the world, internal management turmoil with a changing of the guard put LeBlanc in a leadership role that began to build a strong relationship and trust with the new Patout and by 1975 LeBlanc was offered the job as chief engineer — on a trial basis for a year. Expansion of the mill, continued breakdowns in equipment, the need for key experienced personnel brought 20 years of hands-on experience into play. Environmental laws changed, lost time, bad machine fits — cane was growing and was getting better yield but so many mills were closing that LeBlanc had to meet new demands every day at the mills owned by the Patouts.

Before the end of the decade, LeBlanc had traveled with Billy Patout to Florida, Puerto Rico, the Dominican Republic to purchase machinery and expand the factory, study core samplers and tour sugar industry operations. The only conclusion for grinding more cane was to get bigger.

In 1978 the Enterprise factory was awarded the coveted Buck Horns, an award to the sugar factory that grinds the most cane. The award dates back to 1889 and the Patout mills at Enterprise, Sterling and then Raceland — their big competition. After the addition of the new mill, longevity was Patout’s for the Buck Horns.

After further education at Louisiana State University, LeBlanc completed Energy Utilization in Sugar Factories and Dec. 1981 received a Recognition of Achievement certificate from the Greater Iberia Chamber of Commerce.

“All of the mills were grinding 300-400,000 tons of cane in Louisiana, but whoever thought you could grind one million tons,” LeBlanc said. “That’s when we got the boss a solid silver sugar cup and gave it to him at the American Sugar Cane League. He had a vision and I was his chief engineer. We didn’t stop. It was a big thing.”

LeBlanc said during the interview that right now there is more sugar cane being produced with 11 mills than there was when 50 mills existed.

“All 11 sugar mills need to stay in business to help the economy,” LeBlanc said. “We have the cane and they’re all making a profit — land owners, farmers, sugar mills — if they do it right.”

Throughout the 1980s, LeBlanc was traveling around the U.S. and abroad learning about the industry, starting and managing mills during harvest and purchasing equipment. He even traveled to Honduras several times including as the U.S. Sugar Industry representative for the inauguration of the President of Honduras.

By the end of the decade, he was involved in testing syrup and installed the first force fed roller, built cane carts and completed LSU’s Executive Program. There would still be three decades of sugar cane productivity before LeBlanc would retire.

“I need a journalist to tell all the stories. I have a couple of thousand pictures from traveling more than 30 countries around the world,” LeBlanc said. “I had a 25-year party, 30-year party, 40-year and 50-year party. They kept giving me watches or something. At the last one, the president of the company finally gave me a nice Rolex.”

After all the years, the growth and expansion, LeBlanc can feel good about retiring. He is finishing a plan at all three of the Patout mills — synchronized and aligned with interchangeable parts, continuing to save the company money and working profitably.