New Iberia native Dracos Burke recalls a lifetime of service to country and family.

Published 8:00 am Wednesday, June 9, 2021

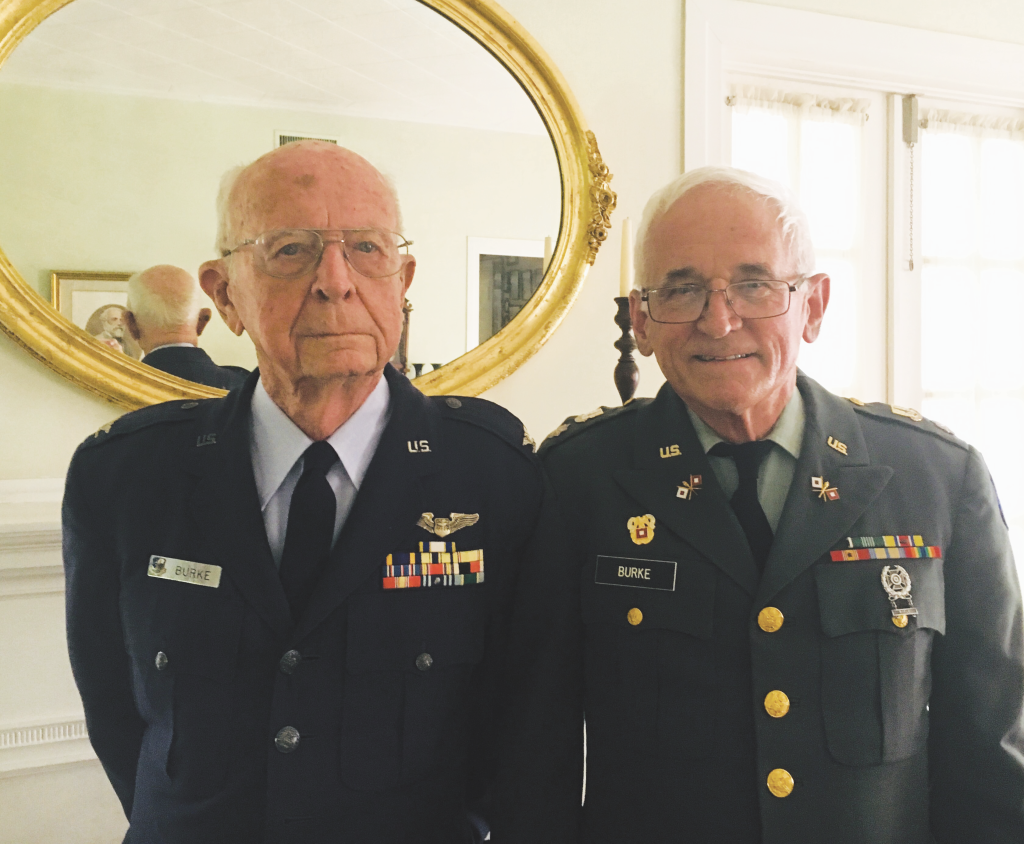

- Mike Burke.png

Retired Colonel Dracos Burke is meticulous in his recounting of a life that has spanned 102 years this September. At first glance his story is one of an honorable military career, but with a little tugging at the layers, Burke emerges also as a husband and father who gave his children what they describe as “experiences of a lifetime.”

Burke was born in 1919 in New Iberia to a rice broker and homemaker, the second of four children. He was exceptionally bright, skipping a grade and transferring from public school to an all-boys parochial school. At 15 he was a page in the U.S. House of Representatives.

When considering his options after graduation, he realized how limited they were. “It was the depths of the Depression at that time, and there was nothing in New Iberia or anywhere else that offered an opportunity to get out and make a living.” He remembers fondly looking at magazine covers of flying aces and watching WWI movies. So, after a few years of college at Southwestern Louisiana Institute (SLI), where he was biding his time until he reached the required age of 20, he enlisted in the U.S. Army Air Corps in early 1940.

A Bombardier and a Man of Words

When Burke first enlisted, World War II had just begun. At the time, he remembers, there wasn’t much thought that the U.S. would become involved in the war. He began flight training at Love Field Texas, but the number of cadet slots were very limited. “There was a high rate of elimination, and I was one of the ones eliminated,” he says with a little chuckle. So, in April of 1940 he returned to New Iberia, where he completed his coursework at SLI and worked at his uncle’s ready-mix concrete company. Unexpectedly he received a letter from the War Department telling him he had been accepted for reinstatement in the flying cadet program. By then the program was expanded to include new opportunities to train as either a navigator or bombardier. He applied for a navigator slot, but was accepted as a bombardier. “I wasn’t going to quibble,” he says. “I wanted to fly.”

Burke was a member of the third class to graduate the program and went on to help open the first bombardier school in Shreveport. He was an instructor in Shreveport when Pearl Harbor was bombed, and he volunteered to be sent to the west coast. Upon reporting for duty, Burke recalls, “The executive officer said, ‘Who are you,’ and we said, ‘We’re the bombardiers y’all wanted so badly,’ and he said, ‘What’s a bombardier?’” They had one airplane, a single engine dive bomber. His time there is not something Burke looks back on fondly. “It was horrible living,” he says. “There were no bathrooms or showers. I ate Christmas dinner in ‘41 out of a tin kit, in a snowstorm, standing up.”

Advance the reel a bit and you’ll see that Burke went on to establish himself as a skilled pilot, an instructor and an officer. The airplanes became more sophisticated (B-25s were his favorite to fly), and new training and strategies emerged. “It was fairly complicated business,” he says. He went on to fly B-17s in Germany, where his executive officer discovered he had a college degree and could write well. There he was named the historian and public relations officer, and he learned how to run a newspaper and a photography lab. He did a stint as public relations officer for the European Air Material Command, as well. In 1947 he was assigned to Davis-Monthan Air Force Base in Tucson, Arizona, a B-29 outfit, where he became the public relations officer of the 43rd Bomb Wing. “There’s no future as a bombardier,” Burke says. “Fortunately I could write.”

Two Law Degrees and a Second Career

Sometime after the war ended, the Air Corps, now reorganized as the U.S. Air Force, set up a program for college graduates to advance their education. Burke was accepted into the program and was sent to law school at University of Denver. He graduated and served as a Judge Advocate in various locations, including Tuscson, Tampa, Shreveport and spent three years in Spain, where he became a colonel. “That was the best deal I ever had,” he recalls.

Burke went on to serve a few years in South Carolina in Tactical Air Command, then as Judge Advocate for the Strategic Air Command at Offutt Air Force Base in Omaha for ten years – the remainder of his tenure in the Air Force. After 30 years of service, he retired from the military at 50 and returned to New Iberia. There he realized he needed to learn Louisiana’s Napoleonic law, so he attended LSU law school and earned a second degree. He accepted a position with the District Attorney’s office, where he served as an assistant district attorney until his second retirement eighteen years later at age 70.

Family Man

Burke speaks of his late wife Carrie fondly and often. “She was a dynamo,” he says. “She was responsible for anything good that happened.” Her family moved to New Iberia from New Orleans, when she was still in high school, and they started dating after visiting with each other in the registration line at SLI. “He helped her set up her classes, and the rest is history,” says Kathleen Haik, number five in the line of Burke children. Early in his military service, he was located at Barksdale Air Force Base in Shreveport, which was close enough to his future wife’s home in New Iberia to visit. They were married in September of 1941 in the old St. Peter’s Church in New Iberia and had six children between 1942 and 1956.

You won’t hear one complaint from the Burke bunch on growing up in their military family. Haik recalls a lifetime of wonder and excitement alongside her military father and adventurous mother. “Life was an adventure,” she says. “I loved watching the planes take off and land. I loved how the base came to a standstill when the flag was raised or lowered at the end of the day.” In the background of their lives were always events like Bay of Pigs, the Cold War and Vietnam. “But there was no fear,” Haik says. “Just a matter-of-fact reality.”

While wife Carrie is described as “fun-loving,” Burke was somewhat strict. Haik says, “With six kids you had to have rules.” Burke recalls the children being well-behaved. “In Spain the three boys were in one room and I treated them like military,” he remembers with a laugh. “In the mornings I made them stand at attention. They had to make their own beds and I did inspections.”

When they traveled or moved, Burke and his wife made sure the kids experienced everything possible, packing their itinerary with fun activities and interesting sights. “We went to lots of places and saw lots of things. The beach. Mt. Rushmore. Denver. Gettysburg,” says Haik. She remembers her parents, in an attempt to enrich the children’s minds and keep them busy, would pay them to learn poetry and recite it back. The TV broke and they didn’t get another one for a long time. They were too busy seeing the world. They didn’t play much by way of organized sports, so their outlet was to play together. With the exception of attending the American schools in Madrid, Spain, the kids always went to Catholic schools. “Finding homes near Catholic schools was always a priority for [my parents],” Haik says.

Legacy

Burke and his late wife have 6 children, 18 grandchildren, 33 great grandchildren and one great-great grandchild. “And that’s changing as we speak,” he says. Three of his sons joined the military, as did some of his grandchildren. He didn’t try to influence them either way, but he knows the benefits of choosing military service. “The people I served with are some of the best people in the world,” he says. “And they don’t all start out that way. Some of them straighten out along the way. I think it’s a great experience.”

It would be hard to quantify the impact Burke has had on his family, his colleagues and his community. But, if you ask any of his children, they will all tell you it was because of him they got to “see the world.”