Darrell Bourque’s poetry reflects empathy – both seen and envisioned.

Published 8:00 am Thursday, July 15, 2021

- AmedeSign.jpg

Sitting in his Church Point home on the land he’s known his whole life, poet Darrell Bourque settles down for our interview. His wife Karen, a glass artist, slips to the back cottage to work on her latest project. We watch as his two cats vie for ruling rights outside. One of his two daughters stops by for a quick visit. It’s a comfortable scene,

as he reflects on two of his most recent and most passionate projects and their influence on his writing.

Early on Bourque might’ve seemed an unlikely candidate for the poet’s life, having grown up in rural St. Landry with limited access to art and education. But it was the strong Cajun culture and a desire to unlock more of his world that pushed him beyond his family property line and into the world.

While he earned his undergraduate and master’s degrees in English from University of Southern Louisiana (now ULL), it wasn’t until he was working on his PhD at Florida State that he was awakened to his connection and talent for poetry. He is a professor emeritus in English at ULL and, over his career, he’s published several books and collections. He’s also been awarded a host of honors, including Artist of the Year by the Acadiana Arts Council (2001), Louisiana Book Festival Writer Award (2014), the Pirate’s Alley Faulkner Society’s ALIHOT (A Legend in his Own Time) Award for Poetry (2014), and the Louisiana Endowment for the Humanities Humanist of the Year Award (2019).

Governor Kathleen Blanco named him poet laureate of Louisiana for a two-year term in 2007, and he was reappointed by Governor Bobby Jindal in 2009.

As poet laureate (which only requires that he hold one reading per year),

he believed he should take advantage of the opportunity to celebrate and promote Louisiana poets throughout the state, organizing numerous creative outreach events and enrichment programs designed to expose people to the art. He has a constant eye out for ways to use his writing for common good and social awareness, and over the past few years found two such ways in a small-town musician and an international organization.

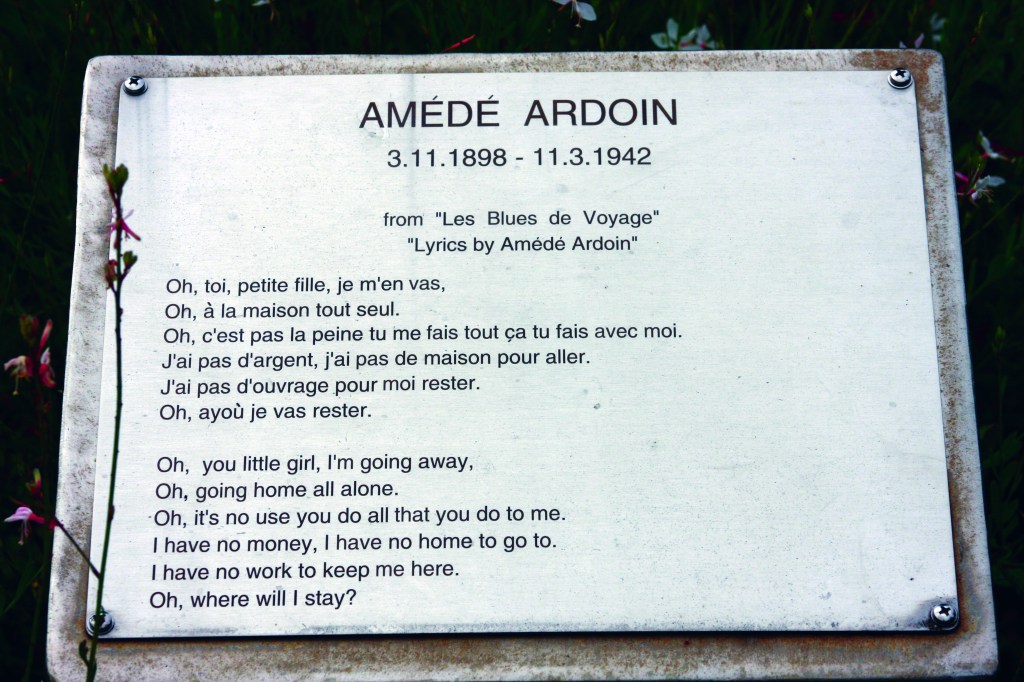

Amédé Ardoin: A Homecoming

Bourque has a long-standing fascination with the cultural and historical figures of Acadiana, in particular Amédé Ardoin, an early Creole musician who died in 1942 under racially-charged circumstances. Ardoin was a pre- Zydeco accordionist and singer who

is now widely credited with melding unique styles and laying the foundation for what would become our familiar Creole music. “Amédé was an important figure in Louisiana. His music is that old call and response music that comes right out of the times of slavery,” Bourque says. “I just became fascinated with him.”

It was when Bourque began writing his book Megan’s Guitar that he became particularly interested in the historical musicians in Acadiana. “Our Cajun and Creole writers were our first poets,” he says. “I became intrigued with the songwriting and the way it has strong poetic elements.”

Ardoin wasn’t the first Creole musician, but he was the first to turn it into a professional career. He lived in a small rural town (likely in or around Eunice) and he only spoke Creole French, yet he travelled to a New York studio and recorded 31 songs during his short

life. He frequently played his music for eager crowds throughout the region and gained a following in both the Cajun and Creole communities.

As the devastating story goes, one evening in 1942, while performing

one of his usual gigs in the Pineville area, he accepted a handkerchief from

a white woman to wipe his brow. Two men in attendance, out-of-towners who were ignorant to the tight-knit Cajun-Creole community, were outraged by what they perceived as a step over the racial boundaries of the times. They followed him home that evening, beat him and left him to die in a country ditch. Although he was found alive and taken to the hospital, he never regained his physical or mental health and died weeks later at 44.

The tragic story still has a palpable effect on Bourque. “My grandmother, who was a widow, was checked on every morning by a Creole man,” he recalls, choking up. “I grew up in a community that is a Cajun-Creole mix, and those two elements cannot be separated.”

But it is really the last chapter of Ardoin’s story that ultimately captured Bourque’s attention and motivated him to act. He learned that in a final insult to Ardoin and to his family,

the musician was unceremoniously buried in an unmarked grave alongside 2,500 other unknown black patients of the Pineville hospital. As Bourque researched Ardoin further, he discovered the man’s family had been trying for years to find his remains to bring him home. While identifying his exact burial spot would be impossible, given the lack of grave markers, Bourque had an idea that might bring the musician home after all: a statue in his likeness that would symbolically return him to St. Landry Parish.

In 2014 he and friend Patricia Cravens, an educator and actor, co-founded the Bringing Amédé Home Project to raise awareness and money for a commissioned statue of the musician. Bourque wrote a collection of poems, invited people over, did readings, told the story and passed the hat. Fundraising was slow at first, but then they got the attention and support of the St. Landry tourist commission board, which eagerly gave them the remainder of the needed funds.

In 2018, after nearly 80 years of being anonymously buried somewhere in a Pineville cemetery, Amédé came home. “We looked at a lot of sites, but felt the best place to commemorate him would be at the St. Landry Parish Visitor Center,” Bourqe says. “We expected 50 people, and there were over 500,” he remembers. “They were people who loved music, who knew the importance of the Ardoin family. And the Ardoin family showed up en masse. It was an incredible event.”

The life-sized, solid steel likeness of Ardoin standing atop his accordian was sculpted by Breaux Bridge artist Russell Whiting. The musician is depicted holding a single lemon in his left hand. “Amede always carried a lemon in his pocket to keep his voice clear,” Bourque explains. That sentiment is further found in another of Bourque’s initiatives. The Lemon Tree Project urges businesses, civic organizations, community groups and individuals to plant lemon trees in honor of the musician. “Not only will there be this statue in his honor, but the lemon trees are a living commemorative to him.”

Narrative 4: Fearless Hope Through Radical Empathy

Another of Bourque’s passion projects is more global in its reach, but equally and deeply personal. In 2012 Bourque and a dozen other writers met to discuss an idea that would help teenagers cultivate empathy and reject stereotypes. “We went up to the mountains one night and we spent the weekend brainstorming,” he remembers. The resulting initiative Narrative 4 (N4) was the vision of its president Colum McCann and CEO Lisa Consiglio, and is now a global network of educators, artists and students working to empower young people to learn how to hear others’ voices and empathize with their stories.

In an innovative methodology, participants are paired with someone from another part of the world, or a different ideology, motivation or philosophy. They exchange their stories with one another one-on-one, sharing the details of their hardships, fears and motivations. The participants each have an opportunity to reflect on their partner’s story, then come

back the next day and tell that story to the entire group in first person. The result is a powerful and moving shift in understanding of the other’s perspective. “It’s a safe space where we can tell our stories and not be afraid of each other,” he says.

N4 explores themes of faith, identity, environment, violence and immigration. They work in 16 countries, with a foundational part of the project being the Artists Network, a group of writers, musicians and visual artists who devise creative and moving ways to empower students for empathetic leadership. The idea being that storytelling (in whatever form) can change the world.

While Bourque was a founding member of the N4 program, his participation has fluctuated over the years. But in 2018, when N4 held their annual summit in New Orleans, Bourque was asked to head up the immigration theme for the kids who came from all over the world: Ireland, Connecticut, Africa, and Nazareth, among others.

“My job was to plan the students’ immigration experience for the summit,” he says. “I brought them into Arnaudville in a bus and asked them to imagine they were immigrants, going into a place and into a culture they had never seen before.” Bourque had the bus drop the group off a mile from the reception and they walked together, discussing the idea of cultures and migration. “I got a group of Native American dancers and singers to welcome them into Arnaudville, as we approached the house,” he recalls. “They brought us inside and had us do the welcome dance, too.”

Throughout the experience, Bourque explains, the Native American group walked with them, reminding them of how it feels to navigate a new culture. They ate Creole food and discussed the cuisine. They met Genaro Smith, an African American -Vietnamese poet and novelist, who told them about growing up as a mixed-race man in America. They met Phoebe Hayes, who talked about forced migrations. And they listened to musician Coleman Thibodeaux play Creole music and tell his immigration story.

Much of Bourque’s recent work has been rooted in strong social activism, “partly because of Narrative 4, which gave me insights as to what I could do to support it.” His last published work, migraré, is one he most associates with N4. “That book was brought on by my thoughts trying to process this whole idea of migrations and immigration and why that makes us so afraid.” He explores images of the wanderer and the wayfarer and how those travellers were always treated well in literature. “But all of the sudden in the 20th century, when a stranger comes into town, there’s all this distrust. And you do just the opposite of what that literature of antiquity tells us to do.” It’s precisely the theme he has helped students work through in Narrative 4.

Bourque’s experiences with N4 are also the impetus for his latest work. “I’m playing around with writing a group of poems that fuses conflicts,” he says. “The tentative title is The Family.” For Bourque the family in his poems is the one he’s been introduced to through Narrative 4: a diverse group of strangers who have come together from disparate places to tell each other’s stories, to give each other a voice and ultimately to meet somewhere in the middle.