Gonsoulins trace their history seven generations back in Acadiana.

Published 8:00 am Wednesday, September 8, 2021

- Gonsoulin map2.png

Shannon Gonsoulin’s story is one of deep roots fixed firmly in the land of his ancestors, a cross-continental search into his rich lineage, and a discovery that his passion for ranching was a destiny set forth by the first Gonsoulin to arrive in Acadiana.

It was important to Gonsoulin and his wife Toni to raise their four children (Taylor, John, Anna and Joshua) in Iberia Parish, where he grew up and where he now operates his cattle ranch. They met as classmates at LSU School of Veterinary Medicine in Baton Rouge and married in 1993, before graduating and starting their lives in Loreauville – just down the road from his family’s property. They are both vets in the Acadiana-area, dividing their time between the ranch and their four clinics located in New Iberia, Morgan City, Franklin and Breaux Bridge.

Trending

The calling to farm cattle was always strong for Gonsoulin, but it intensified around the time he and his wife returned to the Teche area from Baton Rouge. “I was a veterinarian and I rodeoed. I don’t know if that gave me the itch to want to be a cowboy or if it’s in my blood,” he says. “For whatever reason, I always knew I would have a cattle ranch.” He and his family would eventually build their home (a compound of sorts, complete with a “Saloon” in the back) on 300 acres of Gonsoulin land in New Iberia.

Ranching may very well be in Gonsoulin’s blood, but he didn’t really know the strength of his early ancestors’ involvement with cattle until he’d already decided that’s what he wanted to do. He knew a little about his heritage, but there were large gaps. “My grandpa died when I was still fairly young and stupid and didn’t ask the right questions,” he explains.

The exact moment Gonsoulin accelerated his interest in his ancestors is not clear, but after starting his cattle ranch and vet practice, he enlisted the help of his cousins and began looking through his late grandfather’s family papers. “I was intrigued. Here I had the box of family treasures, and it just made me more interested than ever.”

Gonsoulin of Marseille

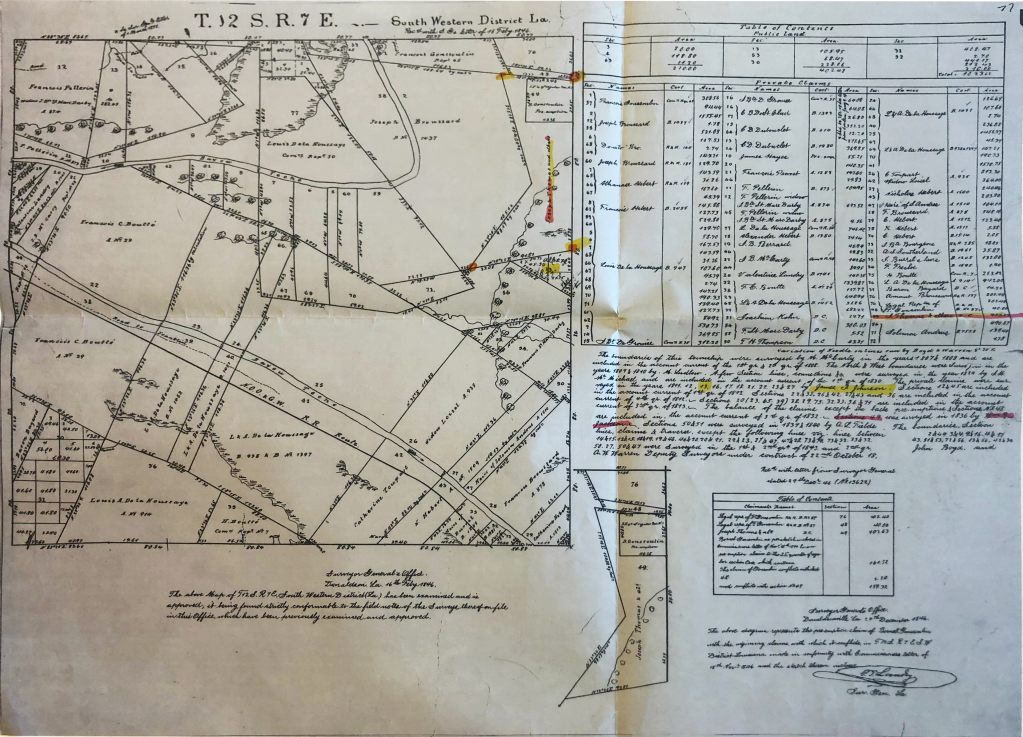

The New Iberia cattle rancher is the seventh-generation Gonsoulin to live in the Teche area. His research into the Gonsoulin lineage revealed the first of his ancestors to arrive was Jean François de Beaumelle Gonsoulin, who came to the United States as a land surveyor for the King of France and decided to stay. François mapped much of the Atakapa District, which is most of St. Martin and Iberia, and was given land grants throughout the District– including a portion on which the family now lives.

According to historical documents (which Gonsoulin found during his research), François settled in St. Martin Parish and started a cattle brand in 1787. Records indicate his “F2” cattle brand was one of the first registered in the area, and one Gonsoulin re-registered and still uses. “People don’t know this, but cattle branding started in the Atakapa region of South Louisiana,” he says. “So we are one of the oldest brands in the United States.”

Trending

As the generations and years went on, ranching and farming was always a part of the Gonsoulin heritage to some extent. Depending on the needs of the family and the demand of their communities, sometimes they used their land for other ventures, like lumber, crawfish, rice and cane. “But it was always an ag-associated type of proposition,” says Gonsoulin.

François’ son Luzin Court was a farmer and rancher by trade, and Luzin Court’s son Euzebe (Gonsoulin’s great great grandfather) also ran a meat market after the Civil War. ”They would slaughter the animals one day, load the meat wagon, then travel to Loreauville to sell or barter meat. And then they’d come back and do it again.” Euzebe’s son Luzin most farmed, but also always had a few heads of cattle, as well.

The two generations immediately before Gonsoulin – his grandfather and father – were the farthest removed from the cattle business for the family. His grandfather (Claude J.) was a military man, who went to officer training school and was a major in WWII, before becoming a teacher back home. While he wasn’t directly involved with managing the land, the property went into cane production during his lifetime. Gonsoulin’s late father (Claude C.) had no agriculture interest and instead operated Claude’ Salvage Yard at the front of the property where Gonsoulin and his family now live.

Serendipity, Luck and a Few Twists of Fate

While Gonsoulin was fairly satisfied with the amount of information he’d learned about his lineage, he still wanted to know more about the first Gonsoulin to arrive in Louisiana – François – and about his Marseille origins. Leslie Gonsoulin Harrington (a New Orleans cousin) had written a book about François called Royal Blend, which piqued his interest even more. The book confirmed what he’d always heard: that François’ original, hand-drawn maps of the Atakapa District were housed somewhere in the U.S. Library of Congress.

It was when a seventh-grade school trip to Washington DC for his oldest daughter Taylor turned into a family vacation that Gonsoulin had his first of two bouts of great luck in his quest. With a healthy dose of self-deprecation, he tells the story of arriving at the front desk of the Library of Congress with a desire to find his ancestor’s maps – and blissfully ignorant of the mountain he’d be expected to climb. “I’m thinking the Library of Congress is like the library down the street,” he says with a laugh. “Let’s go in there and see what they got.”

With his wife and two children in tow, he went into one of the Library’s three buildings and told the receptionist what he wanted; she sent him to the Hamilton Building, where the maps and manuscripts division was housed. “I’m still thinking it’s a regular library,” he admits. But Gonsoulin soon learned the truth of the matter: access to maps is for scholastic research and requires credentials he didn’t possess. After some discussion with Toni, he decided to go through the two-hour background and fingerprinting process anyway, in hopes of coming back to DC one day with his research credentials.

After leaving his family to venture upstairs and complete his task, a man walking through the lobby happened to see the LSU jacket Gonsoulin’s son John was wearing. He stopped and made conversation, asking Toni what brought them to DC. She told him the story of her husband’s quest for information – a “wild goose chase,” Toni says – and the chance meeting became the stuff of a great story. The man was John Thibodaux, from Thibodaux, Louisiana, and he was the director of the maps and manuscripts division of the Library of Congress…and he wrote a book on South Louisiana and used François’ maps in his book.

Thibodaux met Gonsoulin upstairs, explained who he was, and took him through the back of the library to an archive area – an area so restricted, Thibodaux had to scan his retina to enter. Wearing gloves and masks, the two men perused the original, onion-skin survey maps of François Gonsoulin from 1787, complete with field notes written in French and hand-colored detailing. Gonsoulin made copies of every document and left the “library” realizing he’d hit a once-in-a- lifetime lottery of good luck.

But then it happened again. In 2018 he and then-21-year-old daughter Taylor decided to take a cross-country trip in Europe. While on the journey, Gonsoulin planned to stop in Marseille to see if he could find out anything more about François’ father. He knew the Frenchman was a ship captain in the port city, but didn’t know his name or anything else about him. He wasn’t expecting much by way of progress, he admits.

A hint of serendipity began to show immediately after checking into a hotel in Marseille. When he asked at the front desk for the location of the naval archive building, the clerk simply pointed to the building across the street. It was a good start, Gonsoulin thought. But when they arrived, the building was under construction and taped off to the public. Gonsoulin went in anyway and approached the woman sitting at a small makeshift table in the front and, in broken Cajun French, asked for help. She summoned the help of another archive employee and together they finally understood a bit of what Gonsoulin wanted to find. He and Taylor were met with disbelief (or was it pity?) from the employees, but were ushered to another room. “This room was the size of my house,” Gonsoulin recalls. “It had a little bitty desk in the corner and every two feet there were stacks of books as big as Bibles. There were 300 stacks of these books everywhere.” The books, as it turns out, were original handwritten manifests, for years 1500-1800, of every ship that embarked and disembarked from Marseille. “Nothing was digital. Everything was in these books.”

He laughs when he remembers the look on the employee’s face when he asked Gonsoulin for the name of the ship. “I don’t know,” Gonsoulin replies. The name of the man. “I don’t know,” he repeats. What year? With growing determination, he did some quick math and made some assumptions for how old François’ father would’ve been and what years he might have sailed. They narrowed the timeline down to the 1720s to 1730s. Dubiously, the man pointed them in the direction of the corresponding stacks. “He told us we had more chance of winning the American lottery than finding what we were looking for,” he recalls. But he had an hour to search, and forged ahead anyway. He found nothing in the 1720s, but on the third page of the 1730s, daughter Taylor gasped. “She said, ‘Daddy! Gonsoulin!’”

It was the first time he’d seen or heard the name of his early ancestor: Captain Jean Pierre Gonsoulin. They learned he had his own cargo ship that he would use to haul and trade goods. During the conflict between France and Spain, he was boarded by the Spanish Main and had his goods stolen. When he returned to Marseille, he loaded up his ship with cannons and began sailing with the Spanish Armada. He would eventually become a naval captain.

“That kind of stuff never happens,” Gonsoulin says of his good luck. “And it happened twice. Divine intervention happened on both of those days. Without a doubt.”

Gonsoulin Land & Cattle Co.

Over the years, Gonsoulin Land & Cattle (GLC) has grown to 250 head and evolved to offer 100% grass-fed and grass-finished cuts. “When we first started the business, the idea was to sell a few cows to a few neighbors. It was going to be a 30-head venture within Iberia Parish,” he says. Today consumers can purchase directly from the rancher by quarter, half or whole calf, and GLC will deliver anywhere in the Acadiana area (or ship statewide), in whatever cuts the customer wants. “That’s the cheapest way you can buy your meat,” he says. “Some people don’t know about cuts, so we suggest you buy a few different single ones at the GLC store and try them. Flavor profiles are different. I don’t want you buying a whole calf and decide you don’t like the whole calf.”

The ranch maintains steady revenue streams from farmers market sales in Lafayette and Baton Rouge and from their store, located at 6108 Loreauville Rd in New Iberia, but internet sales (glcranch.com) are beginning to take off, as well.

As for what will become of GLC in the coming generations, Gonsoulin knows it’s too early to tell. Taylor, currently an occupational therapist in New Orleans, has expressed a desire to return one day. “She loves the ranch,” Gonsoulin says. “But I know a lot of things can change between now and then.” His youngest Joshua (a junior in high school) has shown the most interest in the ranch and the cattle business. As of now, after graduation he plans to go into the Marines then return to run the ranch. Gonsoulin is hopeful one of them will carry on the family brand.

A Note About Norman

Gonsoulin and wife Toni are pragmatic about the cattle they raise, but there is one rule Toni will not break: if they name a calf, it cannot go the way of the rest of the herd. One sickly calf who was recently pulled and bottle fed back to health is glad for that rule. His name is now Norman, and Toni made Gonsoulin vow to uphold his end of the bargain and never send him to processing. “We made a pinky promise,” she says. “And now he’s a pet.