AR-15: The Rise of America’s Rifle

Published 1:00 am Sunday, June 12, 2022

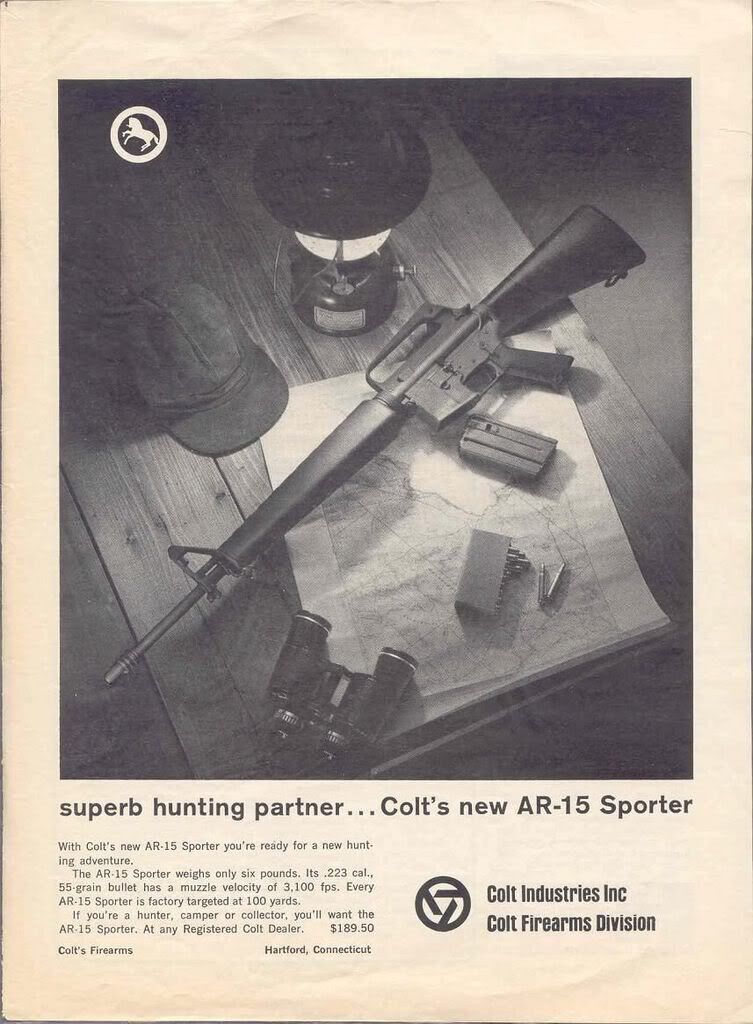

- An advertisement for the AR-15 from Colt

(Editor’s Note: Matthew Louviere, the sports director at The Daily Iberian, is a 2010 graduate of the U.S. Army’s Ordnance School and is certified as a subject matter expert on the small arms and artillery used by the United States military. He has maintained and instructed on the M-16 family of rifles from Alaska to Afghanistan, and is passionate about telling the story of how these rifles came to be.)

AR-15: The Rise of America’s Rifle

Few weapons are as immediately recognizable as the AR-15. What was once a universally hated weapon in the 1950s and ‘60s is now one of the most popular firearms in history, with millions of copies sold to civilians and military forces alike. With political discourse now obsessed with the rifle, an understanding of how a space-age design became the longest serving military rifle in American history will allow citizens to better understand what exactly the AR-15 is, and what it isn’t.

The Beginning, 1945-1965

Following the Allied victory in World War II, the United States began looking at its current small arms inventory and realized it had become a logistical nightmare. In an average infantry battalion, soldiers fielded more than ten different types of small arms with many having their own ammunition requirements that made supplying the troops a massive undertaking.

Clearly, some standardization was in order.

The first thing to be decided upon was the new cartridge the weapons would fire. The Army’s traditional .30-06 cartridge used in the 1903 and M1 rifles was capable of hitting human targets at more than 1,000 yards, but analysts determined that most infantry engagements in the modern era took place at distances less than 300 yards. New technology allowed a shorter, lighter cartridge to be designed that would give almost identical performance to the old .30 caliber round, thus the 7.62x51mm cartridge was born and quickly adopted as the standard small arm cartridge for all NATO forces.

Despite the new cartridge’s technological improvement, it was still a heavy round that produced far more recoil than most other intermediate rifle rounds of the day. The German 7.92 Kurz inspired the Soviets to create the venerable 7.62x39mm, the round that the SKS and AK-47 rifles would eventually be chambered in. With less weight per cartridge, soldiers could carry two or three times as much ammunition for the same combat load. By the time NATO adopted their new .30 caliber cartridge, it was already outdated.

Eugene Stoner, an engineer at Armalite (a division of Fairchild Engine and Airplane Corporation), began working on a radically new weapon design in the 1950s, one that would take advantage of the newest material advancements in aerospace engineering. Chambered in the new 7.62x51mm cartridge, Stoner’s new AR-10 rifle was ready to be presented to the US Army Ordnance Corps for consideration. Despite interest by many outside the military, Stoner’s rifle was just too new for the conservative sensibilities of the Ordnance Corps’ top brass.

Undeterred by the snub, Stoner continued to refine his rifle. The U.S. Army began investigating the use of a smaller caliber projectile in their rifles and asked that Stoner redesign the AR-10 to fire the new bullet.

Stoner would eventually work with Remington to develop the .223 round, which would become the caliber for a new rifle known as the AR-15. The new .223 round behaved differently than traditional rifle rounds, which used their heavy mass to impart energy into the victim. With a bullet that weighed just 55 grains, the .223 could travel at speeds more than 3,000 feet per second and tumble or fragment when it hit human flesh, leaving highly effective wounds that were difficult to repair.

The new rifle and ammunition ran into many of the same problems from the Army leadership, but one officer saw the potential in Stoner’s design. Air Force General Curtis LeMay was blown away by the accuracy and handling of the newly created AR-15, and demanded that the rifle be purchased for Air Force security personnel. The AR-15 had finally gotten into military service.

The Cold War at Home and Abroad 1965-1994

Despite being generally well-received by Air Force personnel in Vietnam, the official adoption of the AR-15, now called the M-16, was a painful affair. Mixups regarding the type of propellant used in the new ammunition caused increased fouling and corrosion in the jungle environment, and the rifle that soldiers were told never required cleaning began to malfunction during firefights. A congressional hearing was held in 1967 to find a solution to these problems, and the M-16A1 was introduced with the correct ammunition. Soldiers fell in love with the rifle, which could spray rounds through the jungle just like the enemy’s AK-47 could, but with less recoil and much better terminal ballistics.

With the kinks beginning to be worked out, the AR-15 was here to stay.

Success and refinement of the rifle in Vietnam led to Colt, who now owned the patent for the rifle, to begin advertising the AR-15 to sportsmen across America. Weighing less than eight pounds with a loaded magazine, the rifle was perfect for varmint hunters and hobby shooters.

The original Colt rifles cost more than what many Americans could afford (the rifle cost $190 in the 1960s, which translates to over $1,400 today), thus the civilian numbers of AR rifles remained low throughout the latter part of the twentieth century.

Design enhancements to the M-16 led to newer models being adopted, though the original method of operation remained unchanged. The United States Marine Corps, who always fancy themselves expert riflemen, demanded that changes be made to the rifle to make it perform better on the marksmanship range. The rear sight was changed to allow easier adjustments to be made in the field, the barrel twist was changed to better stabilize heavier 62 grain projectiles, and the fully automatic feature was abandoned in favor of a three-round burst mode.

The Marines adopted the new rifle first, followed closely by the Army and the other branches. By 1990, the M-16A2 was the standard infantry rifle for the entire United States Military. From South Carolina to Somalia, members of the U.S .Military could be found carrying the new black rifle.

Following the expiration of Colt’s patents, new manufacturers burst onto the scene, lowering the cost of ownership for the AR-15. Suddenly, it became possible for firearms enthusiasts to own a rifle that was nearly identical to the one carried by our armed forces, with obvious changes like semi automatic fire instead of fully automatic.

The Assault Weapons Ban hits America, 1994-2004

In 1994, the Clinton Administration oversaw the passing of a ban on so-called “assault weapons,” a term coined by politicians to refer to military-style semi automatic rifles that they perceived as being used in violent crime across the country. The ‘94 Assault Weapons Ban (AWB) was a blow to the civilian ownership of many rifles, but AR-15 ownership numbers dropped dramatically. Rifles and pistols were limited to ten rounds and many cosmetic features like flash hiders or bayonet lugs, which were standard equipment on AR-15s, were banned outright.

The AWB was given a ten year limit, and in 2004 George W. Bush declined to renew the legislation, opening the floodgates for rifles to find new homes in the hands of millions of citizens who wanted to own these “weapons of war.”

While politicians were neutering the AR-15 at home, the military was refining the weapon further. Since the Vietnam conflict, the AR system had been offered in a short barrel configuration, complete with a collapsible stock to create a small, handy rifle for use by Special Forces troops.

Named the XM177, the rifle saw very limited use during its life cycle. The shorter barrel was much easier to maneuver, but drastically reduced the velocity of the 5.56 round, lowering its effectiveness.

Despite the shortcomings, the benefits of a smaller rifle were too good to pass up, and by 1994 the U.S. Army had adopted the M4 carbine. Sporting a 14.5-inch barrel and a four-position collapsible buttstock, the rifle was perfect for the kinds of urban combat that would become common in the ‘90s.

Updates to the rifle in the form of optics rails and modular handguards meant that the AR-15 was capable of hosting light, lasers, and sights that would increase the user’s effectiveness on the battlefields of the twenty-first century.

The AR-15 in the New Millennium, 2004-2022

Even with the restrictions and bans in place, interest in the AR-15 never waned. Compliant versions were sold that omitted the bayonet lug and flash hider, and magazines that looked like they could hold the regular capacity were limited to just 10 rounds.

Following President Bush’s refusal to renew the AWB, sales of the AR-15 blew away all predictions. According to the FBI, more than 8.6 million background checks were performed in 2003, a year before the ban expired. By 2014, that number had more than doubled. A combination of newly relaxed regulations and manufacturing costs dropping by the day meant that more Americans owned AR-15 than ever before, but with popularity, comes infamy.

The AR-15 was never the gun that most Americans would think of when they pictured a terrorist, but as the rifles became more poplular, they began to show up in more and more crime footage. The features that make the AR-15 great in combat (low weight and recoil, cheap ammunition, good ballistics, and excellent modularity) also made it popular with criminals.

In the years following the sunset of the AWB, despite a continued downward trend of violent crime nationally, the AR-15 became more and more often the weapon used by mass shooters. In the shootings at Sandy Hook, Parkland, Las Vegas, Pulse Nightclub, and now Uvalde, the AR-15 has been used to devastating effect. After each incident, renewed calls to restrict or ban the rifles have gained momentum, and with a Democrat in the White House there is a significant push to enact new gun control legislation before the 2022 election.

So where do we go from here?

After close to 60 years in military service, the U.S. Army has recently announced that it will replace the AR pattern rifle in favor of a piston system designed by Sig Sauer. With AR-15s priced at little as $400 at times, tens of millions have been purchased since 2004 and confiscation on that scale would be an impossible undertaking. Will we see another attempt to pass an assault weapons ban or will some of the alternate proposals, such as a 1,000% tax on AR-15s, become law?

Regardless of what will happen politically, the gun affectionately called “America’s Rifle” will go down in history as one of the most praised and denounced weapons to ever exist.