After Romero’s shrimp boat sinks in high seas, he takes on Gulf to live

Published 7:00 am Tuesday, August 22, 2023

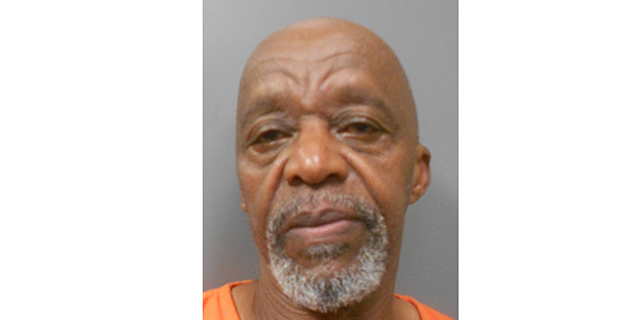

- George Romero of Delcambe, 63, relaxes outside his home four days after he was rescued following a 2-day ordeal that began at 3 a.m. Aug. 10 when his 52-foot shrimp boat , Our Pride, sank and broke up in the Gulf of Mexico a few miles below the mouth of Freshwater Bayou. He's standing next to the wheel of his old 34-foot steel hull shrimp boat and its numbers. He used it for scrap metal after he bought the Our Pride, which sank twice, once during Hurricane Rita and again Aug. 10.

DELCAMBRE – As much as George Romero did to stay alive during a grueling 54-hour period, part of him died a little in the predawn darkness Aug. 10.

That’s when Our Pride, the iconic, 52-foot long wooden shrimp boat he has owned since Fall 2005, sank and was torn apart by wind-whipped waves a few miles off the Gulf Coast near Freshwater Bayou. Romero watched the boat’s demise unfold, then started his journey alone.

Barefoot and wearing only boxer shorts and an inflatable PFD, without food or water, Romero drifted, walked, waded or swam an estimated 19 miles for two days and two nights until 8:30 a.m. Saturday. As exhausted and somewhat disoriented as he was, Romero believed he could make it to an old game warden’s camp along Bayou Fearman on the State Wildlife Refuge.

He’ll never know, though.

Lorrie Ardoin of Lafayette, a charter boat captain who owns Vermilion Bay Charters, intervened to rescue the survivor before the 63-year-old outdoorsman could walk another step. Many are calling it divine intervention because if the relentless southwest wind isn’t blowing, Ardoin’s guide trip with three customers takes him to the Gulf of Mexico side of Marsh Island.

“I definitely think God put me in that place that day. Oh, man, let me tell you, you talk about a survivor! It’s definitely a miracle for that guy he’s still alive,” Ardoin said.

That place was the Horseshoe, also known as Southwest Pass Bay.

“I fish that area a lot but not at this time of year because of the weather,” Ardoin said, adding he was riding there because it was rough in near-offshore waters.

Romero, recounting the story a few days later while relaxing in his home, said, “I heard something. When I turned around I saw an outboard running. Man, I started splashing water, waving. Definitely a sight for sore eyes when I saw him whip his boat around and come straight toward me.”

Ardoin, a 56-year-old retired teacher and basketball coach at Abbeville High School, was scanning the water and horizon for birds pickin’ on shrimp.

“I’m looking. I’m looking. I said, Oh my God! That’s a man waving his arms!’ I started driving to him. He was raising his arms like, ‘Thank you God!” he said. “When I get to him, he was very coherent. As he gets on the boat, I said, ‘Are you OK?’ He was like I was his best partner.”

A sincere, mutual admiration moment followed.

Romero said, “The first thing he told me, he said, ‘Man, you are my hero.’ I said, ‘Bull—-! No. You’re my hero.”

He drank six bottles of water right away, then two more on the boat ride to Cypremort Point, where Ardoin’s friend, Vince Palumbo, picked him up and took him to Delcambre. Ardoin gave him dry shorts and a dry shirt to wear.

Following his return to Delcambre, Romero was persuaded to go to Abrom Kaplan Memorial Hospital in Kaplan, where he got a tetanus shot and more fluids. Hospital staffers also determined the survivor is a diabetic.

When Ardoin, who has been a highly regarded fishing guide since 2019, heard about that diabetes diagnosis, he said, “How he didn’t go into complete shock (during the ordeal) is beyond me.”

The first subject Romero brought up while sitting in his recliner, rehashing the nightmarish sequence, was his family. He talked about his father, his two sons and his stepson. He was oh-so proud of Niles Romero of Abbeville, Jefferson Island Elementary School principal in Iberia Parish; Chase Romero of New Iberia, who works on the state of the art semi-submersible Thunder Horse PDQ oilfield platform in the Gulf’s Mississippi Canyon, and Paul Krato, a chef who lives in Boston.

Thoughts of family kept him going but it wasn’t easy. Nearly half-a-dozen crew boats, a jackup barge and about twice as many oil field helicopters came within sight but apparently didn’t see Romero.

His next topic was Our Pride, also near and dear to his heart.

Our Pride was a cypress wood-framed boat boarded with red Spanish cedar, “a beautiful boat,” he said. After all, immediately following Hurricane Rita, Romero labored night and day to repair his close friend’s boat that was holed and sank on land inundated by storm surge from Hurricane Ida.

When the boat was more seaworthy, his friend sold it to him for $21,000 – no interest, pay when he could. Romero invested beaucoup hours of hard work, TLC and $70,000 worth of equipment in the vessel with a rich history.

Our Pride was built in 1955 in Golden Meadow. Later, a “Mr. Raymond” acquired it, he said, and moored it behind his house along Bayou Tigre. Then the boat was sold to Daniel Richard, a Texan who owned it a few years before selling it to Romero’s friend, Ricky Broussard.

Fast forward so many years later to Aug. 10. Romero’s pride and joy disappeared in front of him as he treaded water with the aid of an inflatable PFD.

Romero, who ran Vincent’s Slaughterhouse for 28 years in Erath, shrimping during fall and spring seasons, often went out 4, 5 days before returning home. They know he’ll call if he gets in trouble.

Nevertheless, Romero’s family had no idea anything was amiss throughout the ordeal. Romero had no time to call or broadcast a distress signal.

Around 3 a.m., while he had the nets down with shrimp running good, 4- to 5-foot waves rocked Our Pride. He blames himself on several fronts for what happened.

“I shouldn’t have been pushing there in the first place. I shouldn’t have been pushing in that weather,” he said.

Wave after wave bashed the boat, bashed him, knocked his eyeglasses off. He rushed inside to get his cellphone but a wave crashed through the door and knocked him into the shower. He climbed atop the cabin.

As the boat floundered and rolled wildly, he jumped in the Gulf. Then a skimmer’s frame “bogged down in the mud” and punched a hole below the boat’s water line. Our Pride, a vessel that brought so many shrimp to the table, went under in less than a minute.

“It sank very rapidly. She went down upright until she hit the bottom. It started bumping and bouncing again. That’s when the boat started coming apart,” Romero said.

While treading water, he grabbed a 15×15 piece of the back deck that floated within reach. It became an impromptu raft the rest of the day and first night on the water. He pried off the ice chest lid, which doubled as a pickin’ table to sort shrimp, from underneath the raft to make a crude lean-to and makeshift sail to help southwest winds push him north and east.

He traveled an estimated 10 miles before the “raft” bumped into the shore the first full night just east of Bayou Cheniere au Tigre. The rest of the journey across sand and oyster bottoms was ahead of him.

Ardoin believes the survivor probably walked past Tee Butte, a popular fishin’ hole for speckled trout and redfish, while traveling east.

Romero said he briefly lost hope after one large, twin-screw crew boat chugged past him, paused, resumed and paused again within a quarter mile before continuing its mission in Southwest Pass. For a split second, it crossed his mind he was going to die.

“I had a little inclination to step into the deep channel and poppin’ the clip on the life jacket,” he said, somberly, noting he was exhausted and couldn’t have swam 20 yards. “Then I said, ‘Man, I’ve got some beautiful grandchildren who I love and need to go see.’ I said, ‘I’m not going down without a fight!’ ”

Niles and Heidi Romero’s three children and Chase and Jonica Romero’s young twins still have a paternal grandfather to hug thanks to the PFD he was wearing that night. Niles bought it online for his dad two years ago from Academy Sports + Outdoors, the elder Romero said.

“If I ever go out at night (on the boat) or it’s rough, I wear one. I recommend the inflatable life jacket to anyone. Those things are great, wonderful and saved my life,” he said.

During this suffocating heat, even after dark, Romero wears just boxer briefs and the life jacket, which he says is lightweight, flat and doesn’t restrict movement. He always hung it on a door frame inside the cabin in order to touch it before the door handle.

It was there when he needed it.

Niles Romero said, “That flotation device saved his life. It was a miracle start to finish.”

Niles Romero has started a GoFundMe in an effort to buy his father another shrimp boat. Go to “Captain George Buy A New Boat” on gofundme.com.