News

‘You can’t get back what you gave’

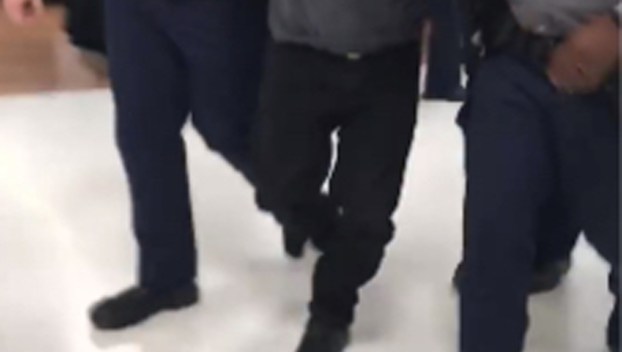

Social media was abuzz Monday after a New Iberia man went screaming down Admiral Doyle Drive on a ... Read more

Social media was abuzz Monday after a New Iberia man went screaming down Admiral Doyle Drive on a ... Read more